DBC Chairman Norman Macfarlane |

Dr. Hornbook |

Gangrel... |

...bodies |

|

|

|

'I once was a maid...' |

'Mair drink!' |

The Bard |

The Sodger Laddie and his Doxy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Merry Andrew |

The Highland Widow |

|

|

John Highlandman |

|

The Fiddler |

|

|

The Caird |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

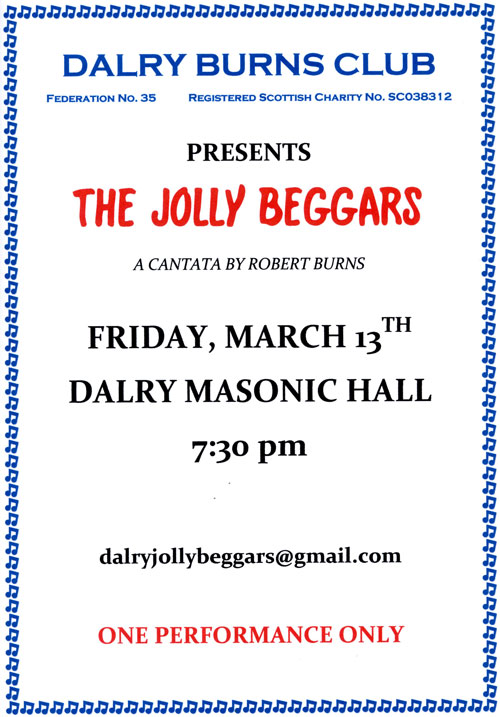

The Jolly Beggars or Love and Liberty, its original title, has been described by Professor David Daiches as Burns' great 'anarchist cantata',

a collection of roaring and joyous character songs linked by 'recitativo' (recitation) narrated in vigorous Scots in a rich variety of complex verse forms. Like 'Tam o Shanter', this great work of musical and poetic genius was a one-off and he never produced its like again. Burns wrote The Jolly Beggars towards the end of 1785 after witnessing a beggars' revel in Poosie Nansie Gibson's tavern in Mauchline, a house of ill-repute and a lodging house for vagrants. Burns and his pals, John Richmond and James Smith, apparently went to see some fun, but the poet was profoundly affected by what he witnessed that night and the result was Love and Liberty, A Cantata. After the bard's prologue, which sets the scene one winter night in Poosie Nansie's , where a band of gangrels / beggars have gathered, we focus on the tale of the ragged one-armed, ane-leggit sodger who, though still ready to follow the flag if needed, now prefers to lie in the arms of his old sweetheart. She in turn sings of how, after his departure to the wars, she was reduced to serving the whole regiment in order to survive, but is now happily reunited with her long-lost 'sodger laddie'. Merry Andrew, the fool, tells us that there are far greater fools than him, especially in the church, court and parliament and then we hear from the widow who has lost her 'braw John Highlandman' and is now reduced to pick pocketing. However, her tragic tale is soon forgotten as she becomes the object of a fierce love rivalry between a merry fiddler, who wishes to charm her with his strings, and a sturdy caird or tinker, who threatens the poor 'gut scraper' with such violence that he is soon forced to turn his amorous attentions elsewhere, leaving the widow to the fearsome 'cauldron clouter'. Finally we hear two songs from the 'care-defying' bard of 'no regard' who firstly toasts the fairer sex and lastly introduces the great anthem of anarchy and defiance, 'A fig for those by law protected'. Burns would have been familiar with the popular cantata form as well as several earlier works like John Gay's 'The Beggars' Opera' or Allan Ramsay's cantata 'The Merry Beggars', and although he used well-known and popular melodies for his songs, Burns is no mere imitator as his work has a vigour and reality all of its own. Yet in contrast to the rich Scots he uses in the recitative to introduce his characters, the gangrels and the bard seem to be singing mainly in English. That is maybe a bit of a contradiction, but, as in many of Burns' works, we often have to ignore the spelling and pay more attention to the rhymes and other sound patterns, so there is in fact a lot more Scots on the page than it often seems. Indeed his English often incorporates Scots and at other times his Scots incorporates English and other languages. He assembles a band of ragged and broken gangrels who can still live life to the full with no care for tomorrow, showing a defiant contempt for a harsh and hypocritical society, all its social codes and conventions and above all the institutions of the state, the law and the church which have betrayed and rejected them. There were then far more beggars around than there are today, but perhaps Burns' work still has a contemporary relevance in reminding us what happens when the whole social fabric breaks down completely. However, if we are to believe what he told George Thomson in 1793, he had forgotten all about it and it was not published until after his death. Obviously it was too radical a work for the repressive political climate which descended on Britain at the start of the war with revolutionary France and Burns had to watch his step in order to keep his job as an exciseman. Burns himself may have tried to belittle it, but many people, including Angellier, the great French Burns scholar, have considered it to be his masterpiece, while Sir Walter Scott claimed that 'such a collection of humorous lyrics, connected by vivid poetical descriptions, is not, perhaps, to be paralleled in the English language.' |